88-195 בדידה לתיכוניסטים תשעא/מערך שיעור/שיעור 1.5

רעיון בסיסי - אינדוקציה על הטבעיים

בשביל להוכיח שטענה מסוימת [math]\displaystyle{ P(n) }[/math] נכונה עבור כל מספר טבעי (למשל [math]\displaystyle{ (1+2+\cdots +n)^2 =1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3 }[/math]) מספיק להוכיח את הבאים:

- (בסיס האינדוקציה) הטענה מתקיימת עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ P(1) }[/math] מתקיים

- (צעד האינדוקציה)אם הטענה נכונה עבור מספר טבעי מסוים אזי היא נכונה גם עבור המספר הבא אחריו. כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ P(n)\Rightarrow P(n+1) }[/math].

למה זה מספיק? בוא נחשוב.. הוכחנו באופן ישיר כי הטענה נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ P(1) }[/math] מתקיים. לכן לפי הטענה השניה, אם הטענה נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] (שזה אכן כך) אז הטענה נכונה גם עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=2 }[/math]כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ P(2) }[/math]. אה! אז עכשיו זה נכון עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=2 }[/math] אז לפי אותה טענה זה נכון גם עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=3 }[/math]! ומה עכשיו? אם זה נכון עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=3 }[/math] זה נכון עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=4 }[/math] . וכן על זה הדרך. אפשר להשתכנע שבסופו של דבר [math]\displaystyle{ P(n) }[/math] נכון לכל [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]

דוגמא: נוכיח באינדוקציה כי הטענה [math]\displaystyle{ (1+2+\cdots +n)^2 =1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3 }[/math] נכונה לכל [math]\displaystyle{ n\in \mathbb{N} }[/math] טבעי

הוכחה:

עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] אכן מתקיים כי [math]\displaystyle{ 1^2=1^3 }[/math]

כעת נראה שאם הטענה נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] כלשהוא, כלומר אם מתקיים [math]\displaystyle{ (1+2+\cdots +n)^2 =1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3 }[/math] אזי הטענה נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math], כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ (1+2+\cdots +n+(n+1))^2 =1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3 + (n+1)^3 }[/math]. כלומר נוכיח ש: [math]\displaystyle{ P(n) \to P(n+1) }[/math]

נוכיח:

[math]\displaystyle{ (1+2+\cdots +n+(n+1))^2=(1+2+\cdots +n)^2+2\cdot(1+2+\cdots +n)(n+1)+(n+1)^2 }[/math]

לפי הנחת האינדוקציה אפשר להמשיך הלאה

[math]\displaystyle{ =1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3 +2\cdot (1+2+\cdots +n)(n+1)+(n+1)^2 }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ =1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3 +2 \cdot \frac{n(n+1)}{2}(n+1)+(n+1)^2 }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ =1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3 +n(n+1)^2+(n+1)^2 }[/math] [math]\displaystyle{ =1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3 +(1+n)(n+1)^2=1^3 +2^3 + \cdots +n^3+(n+1)^3 }[/math]

וסיימנו

דוגמא נוספת:

הוכח כי לכל מספר טבעי [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] מתקיים כי [math]\displaystyle{ 2+4+6+\cdots +2n=n(n+1) }[/math]

פתרון:

עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] אכן מתקיים [math]\displaystyle{ 2=1\cdot(1+1) }[/math]

כעת נניח שהטענה נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] ונוכיח את הטענה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ 2+4+\cdots 2n+2(n+1)=\sum_{k=1}^{n+1}2\cdot k=\sum_{k=1}^{n}2\cdot k + 2(n+1) = }[/math]

לפי הנחת האינדוקציה ניתן להמשיך

[math]\displaystyle{ =n(n+1)+2(n+1)=(n+1)(n+2) }[/math]

שזה הטענה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] וסיימנו.

לפעמים כדאי להניח הנחות חזקות יותר

תרגיל:

נגדיר [math]\displaystyle{ a_0 =0 , a_{n+1}=a_n^2 +1/4 }[/math]/

הוכח כי לכל n מתקיים [math]\displaystyle{ a_n\lt 1 }[/math]

פתרון: נוכיח משהו יותר חזק - לכל n מתקיים [math]\displaystyle{ a_n\lt 1/2 }[/math]

אכן: עבור [math]\displaystyle{ a_0 }[/math] זה מתקיים. כעת נניח שנכון עבור n ונראה עבור n+1

[math]\displaystyle{ a_{n+1}=a_n^2+1/4\lt (1/2)^2+1/4 =1/2 }[/math]

סדר טוב

הגדרה: יהי [math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] יחס סדר חלקי על קבוצה [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math].

[math]\displaystyle{ R }[/math] יקרא סדר טוב אם לכל [math]\displaystyle{ \emptyset \neq B\subseteq A }[/math] קיים איבר מינימום/הכי קטן/ראשון ב [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math].

מינוח: נאמר כי [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] סדורה היטב.

דוגמא: הקס"ח [math]\displaystyle{ (\{1,2,3\},\le) }[/math] היא סדורה היטב - תתי הקבוצות הלא ריקות שלה הן [math]\displaystyle{ \{1\},\{2\},\{3\},\{1,2\},\{2,3\},\{1,3\},\{1,2,3\} }[/math] והאיבר הראשון בכל תת קבוצה הוא בהתאמה [math]\displaystyle{ 1,2,3,1,2,1,1 }[/math].

עקרון הסדר הטוב

נסתכל על [math]\displaystyle{ (\mathbb{N},\le) }[/math] - קבוצת הטבעיים עם יחס הסדר "קטן שווה" הסטנדרטי.

אינטואיטיבית, אכן מתקיים כי לכל קבוצה לא ריקה של טבעיים קיים איבר ראשון - "אם 1 שם, הוא הקטן ביותר; אם 2 שם, הוא הקטן ביותר; ממשיכים כך עד שמגיעים לאיבר כלשהו (כי הקבוצה לא ריקה), והוא הקטן ביותר".

פורמלית, טענה זו, הנקראת עקרון הסדר הטוב, והיא שקולה לטענת (/אקסיומת) האינדוקציה.

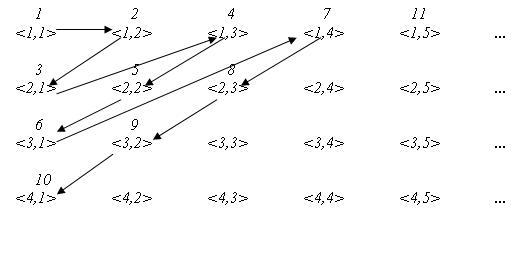

דוגמא נוספת: ניתן להגדיר אל [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Q}_+ }[/math] יחס סדר חלקי לפי התמונה הבא (כאשר מזהים כל שבר עם זוג סדור ומבטלים את החזרות המיותרות)

התבוננו והשתכנעו שזה גם סדר טוב.

הערה: זה בניגוד לסדר "קטן שווה" הרגיל על השברים שאינו סדר טוב כי לקבוצה [math]\displaystyle{ \{x\in \mathbb{Q}_+ | \sqrt{2}\lt x \} }[/math] אין איבר מינימום.

משפט הסדר הטוב

משפט הסדר הטוב קובע שלכל קבוצה [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] קיים סדר טוב.

תרגיל:

תהא [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] קבוצה בת מנייה. הוכח כי ניתן לסדר אותה היטב (בהינתן עקרון הסדר הטוב).

פתרון:

לפי הנתון קיימת פונקציה חח"ע ועל [math]\displaystyle{ f:A\to \mathbb{N} }[/math]. נגדיר את היחס הבא על [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] כך: [math]\displaystyle{ x\leq y \iff f(x)\leq f(y) }[/math]. זהו יחס סדר (השתכנעו!). בנוסף, [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] סדורה היטב על ידו: תהא [math]\displaystyle{ B\subseteq A }[/math] תת קבוצה לא ריקה. אזי [math]\displaystyle{ f(B)\subseteq\mathbb{N} }[/math] תת קבוצה לא ריקה ולכן קיים בה איבר מינימום נסמנו [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]. בדקו כי [math]\displaystyle{ f^{-1}(n)\in B }[/math] איבר מינימום.

הכללות

הכללה פשוטה 1

הכללה ישירה מתבצעת כך (החלפה רק של הטענה הראשונה): אם נוכיח עבור טענה [math]\displaystyle{ P(n) }[/math] ש:

- הטענה מתקיימת עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=k }[/math] מסוים כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ P(k) }[/math] מתקיים

- אם הטענה נכונה עבור מספר טבעי מסוים אזי היא נכונה גם עבור המספר הבא אחריו. כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ P(n)\Rightarrow P(n+1) }[/math].

אז באופן דומה הטענה נכונה [math]\displaystyle{ P(n) }[/math] נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n\geq k }[/math]

כלומר - במקום להוכיח עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] ואז הטענה מתקיים החל מ-1 ניתן להוכיח עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=k }[/math] ואז הטענה מתקיים החל מ-k

דוגמא:

הוכח כי לכל [math]\displaystyle{ x\gt 0 }[/math] מתקיים [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x)^n \gt 1+nx }[/math] לכל [math]\displaystyle{ n\geq 2 }[/math]

פתרון:

עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=2 }[/math] נקבל [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x)^2 = 1+2x+x^2\gt 1+2x }[/math] כי [math]\displaystyle{ x\gt 0 }[/math]

כעת נניח כי הטענה נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] כלשהוא, כלומר מתקיים [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x)^n \gt 1+nx }[/math]

נוכיח עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] מהנחת האינדוקציה נקבל כי [math]\displaystyle{ (1+x)^{n+1}=(1+x)^n\cdot (1+x)\gt (1+nx) (1+x)= 1+nx +x+nx^2 \gt 1+x+nx =1+ (n+1)x }[/math]

וסיימנו

הכללה פשוטה 2

אם נוכיח עבור טענה [math]\displaystyle{ P(n) }[/math] ש:

- הטענה מתקיימת עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] מסוים כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ P(1) }[/math] מתקיים

- אם הטענה נכונה עבור כל המספרים עד מספר טבעי מסוים [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] (כלומר מתקיים [math]\displaystyle{ P(m) }[/math] עבור [math]\displaystyle{ m\leq n }[/math]) אזי היא נכונה גם עבור המספר הבא אחריו (כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ P(n+1) }[/math] מתקיים).

אז באופן דומה הטענה נכונה [math]\displaystyle{ P(n) }[/math] נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n\geq 1 }[/math]

כלומר - אפשר להחליף את ההנחה שמתקיים עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] ולהוכיח עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] בהנחה שמתקיים עבור כל מי שקטן שווה [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] ולהוכיח עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math]

דוגמא:

כל מספר טבעי [math]\displaystyle{ 1\lt n }[/math] ניתן להציגו כמכפלה של מספרים ראשוניים

הוכחה:

עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=2 }[/math] זה נכון כי 2 ראשוני ואז הוא הפירוק של עצמו.

כעת נניח שהטענה נכונה לכל [math]\displaystyle{ 1\lt k\leq n }[/math] ונוכיח עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math]

אם [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] ראשוני - סיימנו כי אז הוא הפירוק של עצמו.

אחרת [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] מתפרק למכפלה [math]\displaystyle{ n+1=ab }[/math] כאשר [math]\displaystyle{ 1\lt a,b\lt n+1 }[/math] לפי הנחת האינדוקציה [math]\displaystyle{ a,b }[/math] מתפרקים למכפלה של מספרים ראשוניים [math]\displaystyle{ a=\Pi_{k=1}^l p_k,b=\Pi_{i=1}^r q_i }[/math] כאשר [math]\displaystyle{ p_k,q_i }[/math] ראשוניים

ואז [math]\displaystyle{ n+1=ab=\Pi_{k=1}^l p_k\cdot \Pi_{i=1}^r q_i }[/math]

וסיימנו

הכללה מעמיקה

תהא [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] קבוצה סדורה היטב (נסמן את היחס שלה ב[math]\displaystyle{ \leq }[/math]) אזי:

- אם [math]\displaystyle{ \forall n ([\forall m\lt n P(m)] \to P(n)) }[/math]

- אז [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] מתקיימת לכל [math]\displaystyle{ a\in A }[/math]

למה זה עובד?

נניח בשלילה כי הטענה [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] לא מתקיימת לכל [math]\displaystyle{ a\in A }[/math] אזי נגדיר [math]\displaystyle{ D:=\{a\in A | P(a)=FALSE \} }[/math] - קבוצת כל האיברים ב [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] שעבורם הטענה אינה נכונה. מהנחת השלילה [math]\displaystyle{ D\neq \emptyset }[/math].

כיוון ש [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] סדורה היטב אזי קיים ב [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] מינימום, נסמנו [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math]. לפי הגדרת מינימום והגדרת [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] נובע כי לכל [math]\displaystyle{ m\lt d }[/math] הטענה נכונה (אם היה [math]\displaystyle{ m\lt d }[/math] שהטענה לא נכונה לגביו אזי הוא היה בקבוצה [math]\displaystyle{ D }[/math] ואז זה היה סתירה לכך ש [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] מינימום של קבוצה זאת).

אבל אם זה כך אז לפי הטענה שמוכיחים זה גורר כי [math]\displaystyle{ d }[/math] כן מתקיים. סתירה. ולכן הטענה נכונה לכל [math]\displaystyle{ a\in A }[/math]

הערה: אפשר לעשות אינדוקציה הנקראת אינדוקציה טרנספניטית על קבוצות כלשהן (לאו דווקא בנות מניה)

תרגילים יותר מעניינים

תרגיל

יהא [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] פסוק. נגדיר בעזרת אינדוקציה פסוקים: [math]\displaystyle{ P_0 = A, P_n=(P_{n-1})\to A }[/math] הוכיחו כי [math]\displaystyle{ P_{n} }[/math] טואוטולוגיה כאשר [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] אי-זוגי.

פתרון: נוכיח באינדוקציה כי לכל [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] אי-זוגי, הפסוק [math]\displaystyle{ P_{n} }[/math] הוא טואוטולוגיה.בדיקה: עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math], הפסוק הוא [math]\displaystyle{ A\to A }[/math]. הוא אכן טואוטולוגיה.

צעד: כעת, נניח את נכונות הטענה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] אי-זוגי, ונוכיח עבור האי-זוגי הבא בתור, כלומר [math]\displaystyle{ n+2 }[/math].

מתקיים:[math]\displaystyle{ P_{n+2}=P_{n+1}\to A=(P_{n}\to A)\to A }[/math] נראה כי זו אכן טואוטולוגיה. ראשית, לפי ההנחה, [math]\displaystyle{ P_{n}\equiv T }[/math] לכל ערך של [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math].

• אם [math]\displaystyle{ A=F }[/math], נקבל [math]\displaystyle{ (T\to F)\to F\equiv F\to F }[/math]- אכן אמת.

• אם [math]\displaystyle{ A=T }[/math], נקבל [math]\displaystyle{ (T\to T)\to T\equiv T\to T }[/math] - אכן אמת.

וסיימנו באינדוקציה.

תרגיל:

יהיו [math]\displaystyle{ A_1,A_2,\dots A_n }[/math] קבוצות אזי [math]\displaystyle{ A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n =\{x| x \; \; \text{in odd number of sets} \} }[/math]

הוכחה:

עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=2 }[/math] זה נכון כי הפרש סימטרי של 2 קבוצות זה כל ה [math]\displaystyle{ x }[/math] - ים שנמצאים או בראשונה בלבד או בשניה בלבד.

נניח כי הטענה נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] קבוצות. נוכיח עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] קבוצות:

[math]\displaystyle{ A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n \triangle A_{n+1} = B\cup C }[/math] כאשר [math]\displaystyle{ B=\{x \; | \; x\in (A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n )\backslash A_{n+1} \} = \{x \; | \; x\in (A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n ) \land x\not\in A_{n+1} \} , \; \\ C= \{ x \; | \; x \in A_{n+1} \backslash (A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n ) \} = \{x \; | \; x \in A_{n+1} \land x\not\in (A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n )\} }[/math]

לפי הנחת האינדוקציה מתקיים [math]\displaystyle{ A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n =\{x| x \; \; \text{in odd number of sets from}\; A_1,A_2\dots A_n \} }[/math] ולכן ניתן להמשיך כך

[math]\displaystyle{ B\cup C = \{x \; | \; x\in (A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n ) \; \land \; x\not\in A_{n+1}\} \cup \{x \; | \; x \in A_{n+1} \; \land \; x\not\in (A_1 \triangle A_2 \triangle \dots \triangle A_n )\} = }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \{x \; | \; x\in \; \text{in odd number of sets from}\; A_1,A_2\dots A_n \; \land \; x\not\in A_{n+1} \} \cup \{x \; | \; x \in A_{n+1} \; \land \; x\not\in \text{in odd number of sets from}\; A_1,A_2\dots A_n \} = }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \{x \; | x\not\in A_{n+1} \; \land \; x\in \; \text{in odd number of sets from}\; A_1,A_2\dots A_n \} \cup \{x \; | \; x \in A_{n+1} \; \land \; x \in \text{in even number of sets from}\; A_1,A_2\dots A_n \}= }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \{x \; | \; x\in \; \text{in odd number of sets from}\; A_1,A_2\dots A_n, A_{n+1} \} }[/math]

לכן, הטענה נכונה גם עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] וסיימנו

תרגיל:

הוכיחו בעזרת אינדוקציה כי כל מצולע קמור (כלומר הצלע בין כל שני קודקודים נמצאת בפנים המצולע) בן [math]\displaystyle{ n \geq 3 }[/math] צלעות ניתן לשילוש (כלומר ניתן לחלק אותו למשולשים) ושיש בשילוש [math]\displaystyle{ n-3 }[/math] אלכסונים.

פתרון: עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=3 }[/math]: מצולע קמור בן 3 צלעות חייב להיות משולש (ייתכן בעיוות כלשהוא) ולכן הוא ניתן לשילוש ע"י [math]\displaystyle{ n-3=0 }[/math] אלכסונים.

כעת נניח שהטענה נכונה עבור כל מצולע קמור בן [math]\displaystyle{ 3\leq k \leq n }[/math] ונוכיח את הטענה עבור מצלוע קמור בן [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] צלעות (כלומר שכל מצולע קמור בן [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] ניתן לשילוש עם [math]\displaystyle{ (n+1)-3 }[/math] אלכסונים). יהא מצולע קמור [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] בן [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] צלעות. נמתח קו בין שני קודקודים שלו. כעת המצולע שהתחלנו איתו התחלק לשני מצולעים קמורים, נסמנם [math]\displaystyle{ M_1,M_2 }[/math]. נסמן את מספר הצלעות של [math]\displaystyle{ M_1 }[/math] ב [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] (כלומר יש לו [math]\displaystyle{ k-1 }[/math] צלעות משותפות עם [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] + הצלע שהוספנו. מספר הצלעות של [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] הוא [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] ולכן מספר הצלעות המשותפות בין [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] ל [math]\displaystyle{ M_2 }[/math] הוא [math]\displaystyle{ n+1-(k-1)=n-k+2 }[/math] ולכן מספר הצלעות של [math]\displaystyle{ M_2 }[/math] הוא [math]\displaystyle{ n-k+3 }[/math]. כיוון ש [math]\displaystyle{ 3\leq k,n-k+3\leq n+1 }[/math] ניתן להפעיל את הנחת האינדוקציה על [math]\displaystyle{ M_1,M_2 }[/math] ולהסיק כי [math]\displaystyle{ M_1,M_2 }[/math] ניתן לשילוש ע"י [math]\displaystyle{ k-3,n-k+3 - 3 }[/math] אלכסונים. צירוף השילושים של [math]\displaystyle{ M_1,M_2 }[/math] יתן שילוש של [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] עם [math]\displaystyle{ (k-3) + (n-k)+1=(n+1)-3 }[/math] אלכסונים כנדרש.

תרגיל:

יהיו [math]\displaystyle{ A_1,A_2\dots A_{m+1} \in \mathbb{F}^{n\times n} }[/math] מטריצות ריבועיות אזי האיבר הכללי של המכפלה של כולם ניתן ע"י הנוסחא [math]\displaystyle{ (A_1A_2\cdots A_{m+1})_{i,j}=\underset{1\leq i_1,i_2,\dots i_m \leq n}{\sum}(A_1)_{i,i_1}(A_2)_{i_1,i_2}\dots (A_{m+1})_{i_m,j} }[/math]

הוכחה (באינדוקציה על מספר המטריצות):

עבור [math]\displaystyle{ m=1 }[/math] זה ההגדרה של כפל בין 2 מטריצות

כעת, נניח שהטענה נכונה עבור [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] כל שהוא. נוכיח נכונות עבור [math]\displaystyle{ m+1 }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ (A_1A_2\cdots A_{m+1}A_{m+2})_{i,j}=\sum_{i_{m+1}=1}^n (A_1A_2\cdots A_{m+1})_{i,i_{m+1}}(A_{m+2})_{i_{m+1},j} }[/math]

לפי הנחת האינדוקציה נמשיך:

[math]\displaystyle{ =\sum_{i_{m+1}=1}^n \underset{1\leq i_1,i_2,\dots i_m \leq n}{\sum}(A_1)_{i,i_1}(A_2)_{i_1,i_2}\dots (A_{m+1})_{i_m,i_{m+1}}(A_{m+2})_{i_{m+1},j} = }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ = \underset{1\leq i_1,i_2,\dots i_m, i_{m+1} \leq n}{\sum}(A_1)_{i,i_1}(A_2)_{i_1,i_2}\dots (A_{m+1})_{i_m,i_{m+1}}(A_{m+2})_{i_{m+1},j} }[/math]

וסיימנו.

אזהרה

אינדוקציה היא כלי חזק אך יש לשים לב כי משתמשים בו נכונה.

דוגמא מפורסמת להוכחת שגויה באינדוקציה היא הדוגמא הבא:

טענה: כל קבוצה של סוסים לא ריקה מכילה סוסים מצבע יחיד.

"הוכחה": נוכיח בעזרת אינדוקציה על מספר האיברים בקבוצת הסוסים.

עבור [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] אכן מתקיים כי קבוצה עם סוס אחד מכילה רק סוסים מצבע יחיד

כעת נניח כל קבוצה עם [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math] סוסים מכילה סוסים רק מצבע יחיד ונוכיח את הטענה לקבוצת סוסים מגודל [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math]

תהא [math]\displaystyle{ H=\{h_1,h_2,\dots h_n,h_{n+1}\} }[/math] קבוצה עם [math]\displaystyle{ n+1 }[/math] סוסים אזי לפי הנחת האינדוקציה [math]\displaystyle{ H_1 =\{h_1,h_2,\dots h_n\} }[/math] ו [math]\displaystyle{ H_2=\{h_2,\dots h_n,h_{n+1}\} }[/math] הן קבוצות שמכילות סוסים מצבע יחיד (כי אלו קבוצות סוסים מגודל [math]\displaystyle{ n }[/math]) ולכן כל הסוסים ב [math]\displaystyle{ H }[/math] ג"כ בעלי צבע יחיד (כי יש חפיפה בין [math]\displaystyle{ H_1 }[/math] ובין [math]\displaystyle{ H_2 }[/math].

חישבו איפה השגיאה (רמז: במעבר מ [math]\displaystyle{ n=1 }[/math] ל [math]\displaystyle{ n=2 }[/math])